By Xander

A strike that didn’t behave like a strike

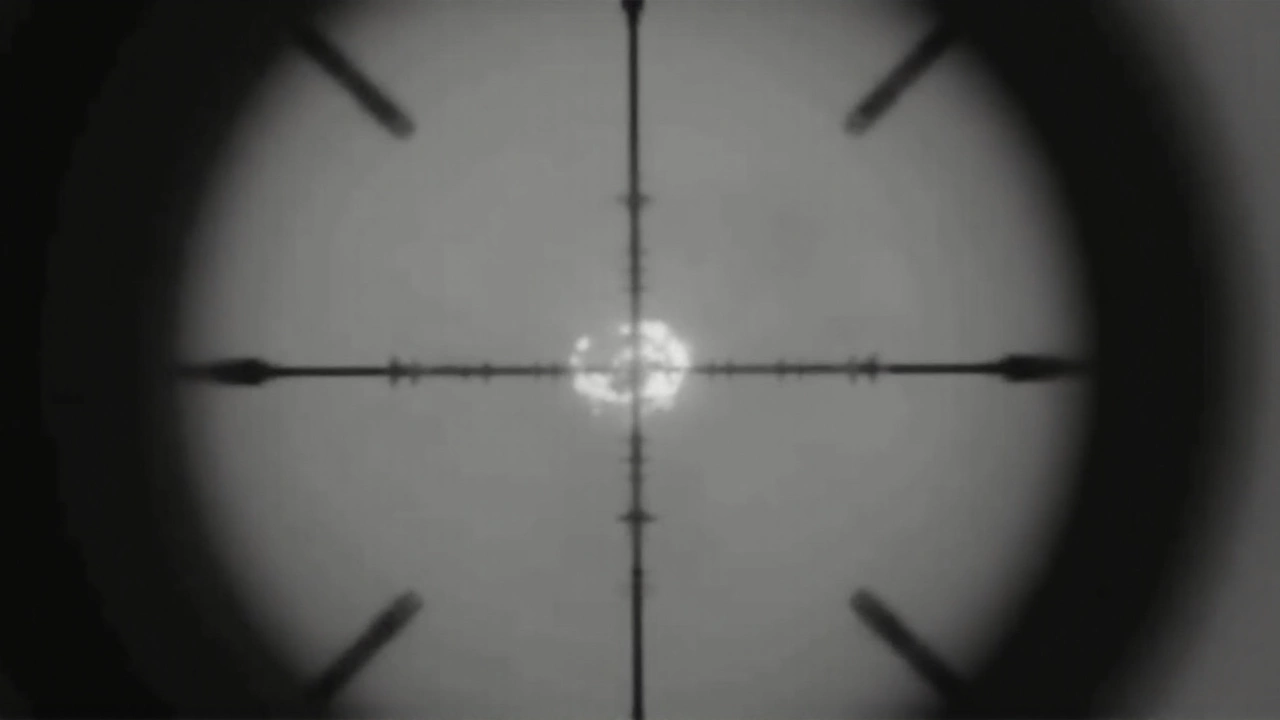

A U.S. drone fired a Hellfire missile at a glowing object over the Gulf of Aden—and it looked like the missile bounced off. That’s what a startling video, played on Sept. 9, 2025, at a House Oversight subcommittee hearing, appears to show. The incident itself happened Oct. 30, 2024, during U.S. military operations tied to Houthi threats against shipping in and around Yemen.

The footage, captured by a U.S. MQ-9 Reaper and provided to lawmakers by a whistleblower, shows a bright, spherical object speeding steadily just above the waves. A missile launched from a second MQ-9 streaks in, seems to strike, and then—rather than detonating as expected—glances away. The object keeps going as if nothing happened. Rep. Eric Burlison, a Republican from Missouri, presented the clip at the hearing.

Former Pentagon official Lue Elizondo did not mince words: “We’ve never seen a Hellfire missile hit a target and bounce off.” He noted that when a Hellfire connects with a solid target, the result is usually devastating. That’s what the weapon was built to do. But the behavior in this video, he said, “defies what we typically see.”

Rep. Anna Paulina Luna asked witnesses if any U.S. system could shrug off a kinetic hit like that. The answer was no. At least, not anything on the books. The Pentagon, for its part, declined to comment when asked by reporters. Key details—what else was in the air, the rules for that mission, the sensor settings, and the weapon’s exact configuration—remain classified.

Journalist George Knapp, who attended the hearing, said there are “servers where there’s a whole bank of these kinds of videos that Congress has not been allowed to see.” That claim fed a broader frustration in the room: lawmakers want the full picture, not just a clip stripped of context.

Why does this matter? Because it lands in the middle of a larger, ongoing push in Washington to figure out what, exactly, U.S. personnel are seeing in the sky and at sea. A recent government tally, cited at the hearing, logged more than 750 new reports of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena between May 2023 and June 2024. The sheer volume has pushed UAP from a fringe topic into a day-to-day national security issue.

What could explain the “bounce”?

Before jumping to the wildest conclusion, it’s worth stepping through what could create a moment like this on video.

First, the weapon. The AGM-114 Hellfire family covers several warhead types and fuze options. Many variants are designed to detonate on or near impact, with different effects depending on the target—vehicles, structures, or small craft. If a fuze doesn’t arm (for example, if the missile fails to meet its required arming distance), a direct hit might behave more like a blunt strike than an explosion. In that case, you could get a glancing contact—especially at an angle—without a visible fireball.

Second, the shot geometry. Missiles close fast and cameras don’t always capture the exact angle. A near miss in low light can look like contact. Sea state matters, too—spray, reflections, and thermal clutter can distort depth perception, especially in infrared footage. What looks like a clean hit might be a grazing pass or a proximity event outside the blast envelope.

Third, the target. The “orb” may not be a solid sphere. It could be a small drone with a bright heat signature, a balloon with a hot payload, or even a sensor artifact that blooms under certain camera settings. Some balloons can carry reflective skins or composite materials that fool tracking algorithms. Small drones can be hard to kill if the detonation happens just off centerline; they may tumble and recover or fly on briefly.

Fourth, the sensor. MQ-9s carry sophisticated electro-optical and infrared systems, but even high-end turrets can create optical illusions—especially at night, over water, and across long distances. Without the native full-resolution file, telemetry, and synchronized feeds from both drones, it’s hard to rule out parallax or processing artifacts.

Now, none of that erases what witnesses emphasized: this clip is unusual. If the missile truly made contact and the target truly shrugged it off with no visible damage, that’s outside what operators expect to see. That’s why lawmakers want the raw data—time stamps, weapon logs, arming status, fuzing reports, and any blast-fragmentation evidence.

Here’s the operational backdrop. MQ-9 Reapers have been flying daily in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden since Houthi forces began targeting ships with drones and missiles. Reapers have ISR duties—tracking threats, spotting launch sites—and they can strike with precision. The Hellfire was designed for armored vehicles and point targets; it’s also used against small boats, crew positions, and hostile drones. In that environment, a fast engagement against an unknown object is not far-fetched.

The big question is provenance. If the object belonged to the Houthis or to another regional actor, U.S. Central Command and its partners will want to know what material and design allowed it to survive. If it was a sensor mirage, the services need to fix that, fast. And if it’s neither—if it’s an unknown platform with capabilities we haven’t seen—that raises urgent questions about air defense and rules of engagement.

Knapp’s line about “banks of videos” points to a second issue: access. Congressional investigators have repeatedly complained about slow walks and partial disclosures. Getting a single clip without its metadata is like getting a single page torn out of a flight recorder. Lawmakers signaled they want the original files, not compressed copies, plus mission packets and after-action reports.

There’s also the broader UAP process. The Pentagon’s All-domain Anomaly Resolution Office (AARO) has said it has found no verified evidence of non-human technology in the cases it closed. At the same time, it continues to receive new reports from aircrew and ships at a steady pace. The Yemen case sits in that tension: a baffling video, a lot of open questions, and a system that is still learning how to capture, analyze, and release data without compromising operations.

Technical analysts who review weapon footage for a living will focus on a few specifics:

- Telemetry: exact coordinates, range-to-target, closure rate, and fuze arming status at the moment of “impact.”

- Sensor settings: IR versus EO, zoom levels, stabilization mode, and any auto-gain that could create bloom or glare.

- Weapon data: missile variant, fuze type, time-of-flight, and whether the guidance made last-second steering commands.

- Battle damage assessment: follow-on tracking, debris in the water, secondary signatures, or loss-of-power indicators.

- Cross-cueing: feeds from the second MQ-9, other aircraft, or ships to confirm geometry and timing.

Right now, the clip is a Rorschach test. To some, it suggests a level of technology beyond what’s publicly known. To others, it’s a textbook reminder that combat footage without context can mislead. The way to settle it is basic: release the raw files to the proper committees, bring in the operators who flew the mission, and let qualified analysts walk through the data frame by frame.

One practical point: if this was a fuze issue, the services will want to know quickly and broadly, because the Reaper community relies on the weapon in a mission set that leaves little room for dud shots. If it was a near miss disguised as a hit, training and targeting procedures might need tweaks to reduce false kills. And if it was a genuine hard contact with no effect, that’s a survivability profile the Pentagon has not advertised—and would want to understand immediately.

Lawmakers said they intend to keep pressing for more material. The Pentagon’s public silence so far isn’t unusual with an active, classified operation. But the longer the gap between what Congress saw in a committee room and what the public can evaluate for itself, the louder the questions will get—about the object, the missile, and the systems meant to tell us the difference.